Thursday, March 30, 2006

Wyatt Earp, Annie Oakley and Me: II

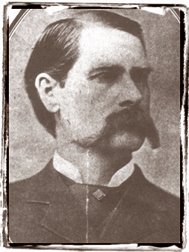

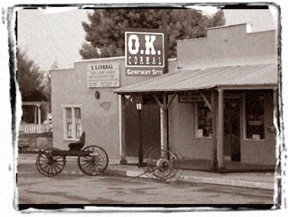

Wyatt Earp, the great, great nephew of the Wyatt Earp of American West legend, is a man whose heritage enters a room ten feet ahead of him. But aside from being the Midwest’s living link to Tombstone, Arizona and the OK Corral, he is a former coworker and dear friend of my Other Half.

Wyatt Earp, the great, great nephew of the Wyatt Earp of American West legend, is a man whose heritage enters a room ten feet ahead of him. But aside from being the Midwest’s living link to Tombstone, Arizona and the OK Corral, he is a former coworker and dear friend of my Other Half.Not surprisingly, he is also a master of firearms – a self-defense and safety trainer. Our reasons for wanting to meet one another were twofold: he wanted to meet his friend’s love interest and I wanted to overcome a fear of guns that was nearly phobic, compliments of a childhood trauma.

Wyatt arrived at the shooting gallery ahead of us. We entered the building and he emerged from the shadows at the far end of the room. There was no piano music in the background or swinging saloon doors. He wasn’t bedecked in a ten-gallon hat or spurred boots. But, he did sport a .45 caliber aura and very Earpish mustache. The small, humid gallery was, obviously, his playground and comfort zone. And, the staff made it clear he carried something like celebrity status there.

Wyatt arrived at the shooting gallery ahead of us. We entered the building and he emerged from the shadows at the far end of the room. There was no piano music in the background or swinging saloon doors. He wasn’t bedecked in a ten-gallon hat or spurred boots. But, he did sport a .45 caliber aura and very Earpish mustache. The small, humid gallery was, obviously, his playground and comfort zone. And, the staff made it clear he carried something like celebrity status there.He and the Other Half exchanged sarcastic quips, introductions were made and the three off us settled into a plush sofa in the trophy room. As the two men visited old times together, with the kind of comfort and ease good friends share, I was happy to simply observe, in awe.

I’ve had similar experiences – and perhaps other adoptees have as well. There is something about seeing the physical resemblances between family members that will sometimes strike me as simply amazing. I perceive it almost like it is an anomaly, perhaps because it is so foreign to my frame of reference. While no one would pass my Wyatt Earp on the street and make an immediate connection to his uncle, connecting the genetic dots was easy for me to do. You could see it in his eyes and in his mustache-framed mouth. But more substantially there was just a cadence to his whole being; his speech, his mannerisms, the way he carried himself that simply dripped history and heritage.

I was probably cured of my phobia before we ever entered the shooting range. Nothing inspires one to leave their gun fears at the door more than having Wyatt Earp hand you his shotgun and say, “lets see what you can do.”

I was probably cured of my phobia before we ever entered the shooting range. Nothing inspires one to leave their gun fears at the door more than having Wyatt Earp hand you his shotgun and say, “lets see what you can do.”But, prior to my first trigger pull, we shared an hour of training: the psychology of using a gun, the way to do it safely and within the law, the idiocy of bluffing and the power of conviction. And as he shared his philosophy of gun ownership it was obvious the wisdom he imparted was from more than training or experience. His knowledge was also rooted in biology and history, the culmination of growing up an Earp, surrounded by tradition and the story of his elders.

While I made tight patterns on targets and blew away silhouettes, it was clear I’d accomplished more than overcoming a fear. I was good. I kept up with my experienced companions, much to their surprise. But bringing home my trophy targets was the least substantial experience of the day.

While I made tight patterns on targets and blew away silhouettes, it was clear I’d accomplished more than overcoming a fear. I was good. I kept up with my experienced companions, much to their surprise. But bringing home my trophy targets was the least substantial experience of the day.When Wyatt looked at me and said, “I think I’ll have to start calling you Annie Oakley,” it finally happened. Time collapsed and, for the first time, with Wyatt Earp unknowingly loaning me his heritage to use as a bridge to history, I felt grounded in both the past and present in the same moment. The experience is now filed away as one of the most memorable of my life.