I remember the kitchen in the farmhouse as enormous; tall and wide, the table long enough to host a small army and the counters built for giants. In my mind, I see the room from the child-high perspective from the dining room doorway: table to the left, kitchen to the right.

I remember the kitchen in the farmhouse as enormous; tall and wide, the table long enough to host a small army and the counters built for giants. In my mind, I see the room from the child-high perspective from the dining room doorway: table to the left, kitchen to the right.I couldn’t tell you where refrigerator stood, the stove was placed or if the floor was tiled or linoleum. I just remember one drawer – the top drawer on the far right, so far off the ground I had to stand on my tippy-toes to peer inside. That drawer held the strangest of treasure, an indulgence bringing excitement and guilt, an item provoking a curiosity I neither understood nor could pull myself away from . . .

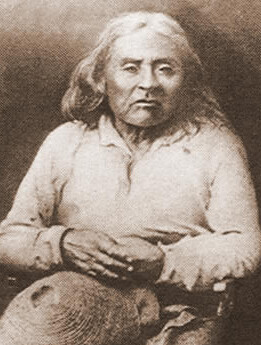

The Palouse County phone book. It wasn’t the book’s contents I found fascinating but the cover. A photo of Chief Sealth. S-e-a-l-t-h, Sealth. I remember sounding out his name and staring into his face as if he and I shared some kind of sacred bond. I was four years old, stealing away into the kitchen whenever I could to share a moment with the Chief, but never in the presence of my mother. I held no explanation for my fascination with his wrinkled face and knowing eyes, but was sure my interest, in some way, betrayed my adoptive family.

My third grade teacher, Mrs. Ellsworth, was a large woman with smooth olive skin and jet-black hair. She was a Blackfoot Indian. I remember her once taking off her sandals and showing us the bottom of her feet – to prove to a classmate her tribe’s name didn’t derive from their color. “Look,” she said, “normal feet, just like yours.” The day Mrs. Ellsworth brought her son to school was the first time I remember thinking it was possible I could be Native American. He was a toe-headed, light-skinned, blue-eyed kid like me.

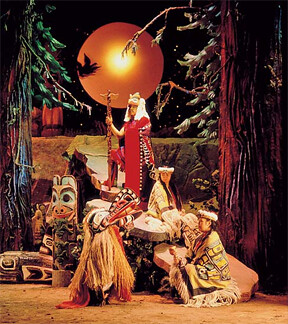

At the age of nine, my adoptive mother took my brother and me on a day trip to Tillicum Village, on Blake Island in the San Juans, where Northwest Coastal American Indians perform traditional dances in a cedar longhouse while tourist dine on salmon baked above open fire pits. I was lost in the ambiance, mesmerized by the Nuu-chah-nulth ancestral masks worn by the performers. I didn’t want to go home. It wasn’t until researching this piece I learned that Blake Island was the birthplace of Chief Sealth.

At the age of nine, my adoptive mother took my brother and me on a day trip to Tillicum Village, on Blake Island in the San Juans, where Northwest Coastal American Indians perform traditional dances in a cedar longhouse while tourist dine on salmon baked above open fire pits. I was lost in the ambiance, mesmerized by the Nuu-chah-nulth ancestral masks worn by the performers. I didn’t want to go home. It wasn’t until researching this piece I learned that Blake Island was the birthplace of Chief Sealth.My adoptive family boasts about the immigration of their ancestors to their Pacific Northwest homestead, still in the family more than one hundred years later. They once owned miles of the best land in town, acreage fronting the Snoqualmie River to the South and stretching West to the confluence of the Snoqualmie and Tolt rivers. They carry that history like a badge of honor. But the story never told is that of the land’s original owners: the Snoqualmie Tribe who lived on the banks of the rivers for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans.

Watered-down history books say the tribe willingly volunteered the land fifty years prior to my adoptive family’s arrival. But it has never escaped me who the rightful owners of that beautiful land are. And, as a child, I never tired of hearing my great-great aunt Gurina, who was born there, tell stories of the Indian women knocking on her front door to trade goods for dairy products and vegetables in the early 1900s.

Watered-down history books say the tribe willingly volunteered the land fifty years prior to my adoptive family’s arrival. But it has never escaped me who the rightful owners of that beautiful land are. And, as a child, I never tired of hearing my great-great aunt Gurina, who was born there, tell stories of the Indian women knocking on her front door to trade goods for dairy products and vegetables in the early 1900s.My attraction to American Indian culture remains unexplained, but unwavering. Certainly, my early years in a rural farming community didn’t lend itself to multi-culturalism, nor did my parents’ insistence I was 100% Norwegian spawn some fantasy about being separated from my tribe. My fair skin and blonde curls implored me to blend in perfectly with my adoptive relatives. Still, at some point I began looking forward to the day I might reunite with my birthfamily and find, somewhere on the family tree, a branch validating a fascination seemingly spawned from nowhere.

But post reunion, when I was given a four-generation maternal family tree and instructed to ignore the obviously Polish name at the top (and also learned I wasn’t a stitch Norwegian), I realized family trees are subjective things. My maternal family is insistent upon being 100% Ukrainian, even if it defies evidence to the contrary.

My paternal family tree remains somewhat mysterious. Third-hand information says I am Swedish and Welsh on that side. My paternal half-brother embraces the Swedish and rejects the Welsh. I seem to be the only one who notices our father’s dark skin and darker hair. If my birthfather carried a secret about a Native American ancestor, he took it with him to his grave.

Family trees are dependent upon what a family is willing to reveal, but new DNA technology offers a truth serum. When genetic testing for ancestral origins became available I considered ordering myself a lab kit, then was crushed to discover that, being female, I carry only the genetic markers to trace my maternal line. Uncovering my father’s ancestry requires the DNA of my brother.

My brother: also abandoned by my father. My brother: with a “proud to be Swedish” bumper sticker adorning his truck. My brother: who happily sits amongst our family, keeping me a secret, complacent in the act of sparing them the knowledge our father fathered a bastard-child. My brother: with whom I share so much but will forever be divided from by his legitimacy. My brother: who hasn’t phoned in six years.

More than stubbornness stops me from picking up the phone. I will not beg him for a thread of my own genetic fabric. The cost of doing so will be a directive to value other things and show gratitude for the smidgens of information he smuggles away from the family gatherings to share with me. My brother is the gatekeeper of my family tree and I simply refuse to sell my soul to get my hands on the key.

I would feel like the women of the Snoqualmie Tribe, forced to beg for bits of the crops grown on land rightfully belonging to them.

That doesn’t mean I must ignore the pull I feel towards American Indian culture. Leaving it isn’t a choice; it steers me.

Last Spring, I attended a talent show at my son’s school. For most of the audience, it was an evening of giggles and applause but, for me, the entertainment stopped when a family walked upon stage – four generations of American Indians wearing traditional dress. The great grandfather took his place at the drum, the lights went down and the fathers, mothers, aunts, uncles and children danced around the drumbeat, singing in an unfamiliar language. One didn’t have to understand the words to recognize the passion of their song; to know they were calling out to ancestors and celebrating their roots, their connectedness.

Last Spring, I attended a talent show at my son’s school. For most of the audience, it was an evening of giggles and applause but, for me, the entertainment stopped when a family walked upon stage – four generations of American Indians wearing traditional dress. The great grandfather took his place at the drum, the lights went down and the fathers, mothers, aunts, uncles and children danced around the drumbeat, singing in an unfamiliar language. One didn’t have to understand the words to recognize the passion of their song; to know they were calling out to ancestors and celebrating their roots, their connectedness.It took my breath away. It wasn’t until the drumbeat stopped and the applause began I realized my body was frozen in rapture and my cheeks were wet with tears.

A DNA swab will not prove or disprove whether or not those tears are real. They speak for themselves.

-

At 2:29 PM, Dazd

-

At 8:31 PM,

Rhonda that was an incredable post. I remember my hardest assignment in school was in grade 4 when we were asked to do family trees. And I remember the hell I endured because I did not want to do my adoptive families history I wanted to do mine.

I , once again , relate to it on so many levels. especially this part

"..More than stubbornness stops me from picking up the phone. I will not beg him for a thread of my own genetic fabric. The cost of doing so will be a directive to value other things and show gratitude for the smidgens of information he smuggles away from the family gatherings to share with me. My brother is the gatekeeper of my family tree and I simply refuse to sell my soul to get my hands on the key."

It really is hard enough growing up adopted than to have others add to it by lording over us the information and knowledge we so despirately crave and deserve. Why are we continually punished for things done regarding us that were always beyond our own control.((HUGS)) -

At 8:46 PM, Attila the Mom

-

At 11:27 PM, elizabeth

-

At 7:20 AM, Mia

-

At 2:14 PM, Kim Ayres

That's a beautiful post Rhonda.

The adoptive world is one about which I know nothing other than snippets I pick up from the likes of yours, Attila's and Quinn's blogs. Problems with "legitimate" relatives seem to be commonplace, but it's something I utterly fail to comprehend. If I was to find out I had another brother or sister out there, I would want to know about them, to meet them. It's sad to hear that there are so many people who think otherwise.

I'm not aware of any Welsh, Swedish or Native Indian ancestors, but go back far enough and we'll be related. So I'll call you a distant cousin and be pleased that I found you. -

At 3:23 PM, Rhonda

Welcome, Dazd. Glad you found something you liked here.

Quinn, you are right. Perhaps the biggest frustration of being an adult adoptee is that we are still at the mercy of others as to how much of our own information we are allowed access to. For me, I have had to remove myself from being at their mercy, even if it means never learning all the things I'd like to know.

Hey ATM, thanks! Now I just need to catch up on reading all my favorite blogs.

Elizabeth, I am not surprised, either, to learn your acestors walked the streets of Paris!

Hugs back, Mia. Your writing always has the same effect on me too. I am always glad you are with me on this journey, even if I wish it was one you never had to take.

Hi Kim, With the exception of one sister, my brothers (3) all wanted to meet me and were quite welcoming. The stopper to all those relationships though seemed to be the sheer amount of time we lost prior to knowing of each others' existence.

Thanks for the comment, 'cuz ;O) -

At 7:43 PM, Kevin Charnas

-

At 6:21 PM, Ruth Dynamite

-

At 3:00 PM, ditzymoi

That statement about your brother being the gate keeper really seemed similar.

I was the only sibling of 6 given up for adoption. Long story shortened, when I found all my brothers and sisters I was so happy ! I was connected to someone. It didnt take long to figure out that my oldest sister was the keeper of information and pictures and she wasnt willing to share either. I think it made her feel important ... thanks to her i dont have any pictures of my parents or brothers and sisters and I REFUSE to ask her for a damn thing. *sigh* -

At 10:31 AM, Pendullum

That was a wonderful post Rhonda.

I have read it three or four times since you have posted it and I am at a loss for what to add to it.

I know that if I had a brother and a sister out there I would want to meet them...

So sad that they think otherwise. It is a real loss... and when dealing with a loss words seem to be of little condolence...

Bit I am so sad for their/your loss. -

At 2:14 PM, Rhonda

-

At 12:22 PM, Sven

Beautiful.

Although I don’t share the adoptive experience with you I can resonate with your inability to trace portions of your family tree. My paternal grandfather died before I was born. Emigrating from Poland, he came to MN along with thousands of other Eastern Europeans looking for work in the local packing plants. Because he found refuge in a familiar cultural community he made no overt effort to “Americanize” as it were.

Unfortunately, he was also less than forthright with information about his past. While reviewing census data from the early part of the 20th century my father and I were able to determine approximately when he came to the US. However, some of the information he recorded was obviously not true (such as English literacy) so we were left to question much of what we found. He was no less guarded in person. The result was a mountain of unanswered questions upon his death.

In 1979 my aunt traveled to Poland in an effort to uncover what she could about our past. She managed to find the town from which my grandfather was believed to have come. Sadly, thanks to Mr. Hitler's very thorough bombing campaign, any historical records (and the churches in which they would have been kept) were destroyed. Aside from the travel experience, she returned with little more than she started.

As for Native American culture, I too share a certain reverence. However, rather than an unspoken sacred bond, my affinity was born out of a personal and professional connection via members of the Tlingit, a first nations people in the Yukon. I spent a few years studying peacemaking circles with two very generous and humble men. Although it has been a few years, their wisdom and compassion will remain with me forever. -

At 5:04 PM, Rhonda

Sven, thanks for sharing your story here. It not only validated my suspicion that family trees are subjective, even when adoption isn't involved, but it was very moving. I wish you could have learned your history and can certainly relate with the frustration of being unable to.

And I'd love to heard more about your experience with the Tlingit. Both subjects would make wonderful posts (hint, hint!)

Thanks, Sven -

At 12:32 PM, Kim Ayres

-

At 9:15 PM, Senior Mom

-

At 5:48 AM, Mel

-

At 10:56 PM,

Hi Rhonda,

I want to echo what everyone else has said. I really enjoyed reading your blog, and couldn't help but think about my own situation being somewhat similar. I'm a transracial korean Adoptee. And I totally know what you're talking about at the end...I was never really brought up on Korean culture by my two parents. It was all about blending in with the dominant culture which was white. But more recently Korean culture, has become much more important and has been kind of putting my entire life into perspective. I visited Korea last year, and nothing prepared me for the attachment I felt for a country that I had such little time living in. Well thanks so much for sharing your story. As adoptees we all have very similar stories, and I'm glad to see that you too are sharing. I made sure to put a link from my blog to yours!

A wonderful post...I will be returning!