PART I

PART IHeritage: adoptees covet it, are puzzled by it and even sometimes dismiss it. People who don’t lack a bloodline, who simply harbor it, like blue eyes or broad shoulders, might never consider heritage because it’s always been there. And they don’t always understand an adoptee’s quest to connect with their own. “What’s the big deal?” some ask, “It never mattered to me.”

I question that.

Perhaps heritage is something not missed until it’s lost; not coveted until it’s been taken away, isn’t even considered because it doesn’t have to be. It’s like breathing. One doesn’t think about taking a breath and then exert the effort to do so. It just happens, it just is – until it isn’t. And then, suddenly, it becomes the most important thing in the world.

Growing up adopted, claiming a heritage has never been a rote exercise for me. It has always been a surgical, copy and paste exertion. The experience of feeling simultaneously grounded in history and existing in the present has always evaded me, despite all the mental gymnastics I’ve attempted to make it otherwise.

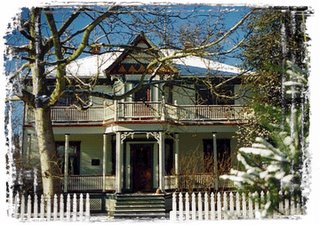

My adoptive relatives were gurus of their heritage. Every household was a shrine to it, every wall and bookshelf a museum of photographs, family trees and memorabilia. My aunt and uncle – who I lived with much of my childhood – lived in the same farmhouse and worked the same land built and cultured by their Norwegian ancestors. I grew up in a literal historical landmark. We even had tourists.

I pasted myself into their bloodline, in part because it is human nature to want to connect in such a significant way and, in part, because it was expected of me. I was chosen for this family based almost solely on my purported Norwegian background. They, perhaps, needed to legitimize our connection as much as I did, so insisted somewhere back in time our respective ancestors merged, thus legitimatizing our connection to one another. So I called myself Norwegian, and when the tourists rang I could impart the family history pitch as well as my legitimate cousins.

I pasted myself into their bloodline, in part because it is human nature to want to connect in such a significant way and, in part, because it was expected of me. I was chosen for this family based almost solely on my purported Norwegian background. They, perhaps, needed to legitimize our connection as much as I did, so insisted somewhere back in time our respective ancestors merged, thus legitimatizing our connection to one another. So I called myself Norwegian, and when the tourists rang I could impart the family history pitch as well as my legitimate cousins.In my first conversation with my natural mother, I learned I wasn’t one stitch Norwegian. Of all the fictional character traits of my father she’d given the social workers to throw them off track, this one carried the steepest consequences. As an infant, I’d been slated to leave foster care for adoption by another family. But when my very Norwegian adoptive parents’ file landed on the social worker’s desk, she changed plans. She was a woman revered for creating the perfect adoption matches, for blending families by their physical and biological similarities so well that a smooth transition for the adoptee was almost guaranteed.

I struggled with the realization the abuse I suffered in my adoptive home might not have occurred had the word “Norwegian” never been uttered in front of a judge. But the bigger struggle was managing the erasure of something that had become a central part of my identity. No longer Norwegian, I tried to adapt to learning I am instead Ukrainian, Swedish and Welch (while being told to “pay no attention” to an obviously Polish name on my new family tree – or to my birthfather’s unmistakably German name.)

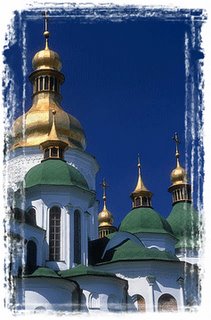

When my birthmother prepared a traditional Ukrainian meal to celebrate my first post-reunion birthday, the maternal side of the family gathered around a table scattered with traditional fare. They shared memories of gatherings past. They told stories. They knew how to pronounce the names of the dishes we ate (and giggled at me uncontrollably when I continually botched attempts to do the same.) They spoke of their Ukrainian grandmother, the old farm, the Old Country. Their words filled the room around me like a thousand snapshot images. I grasped for something recognizable, something to seize and call my own.

When my birthmother prepared a traditional Ukrainian meal to celebrate my first post-reunion birthday, the maternal side of the family gathered around a table scattered with traditional fare. They shared memories of gatherings past. They told stories. They knew how to pronounce the names of the dishes we ate (and giggled at me uncontrollably when I continually botched attempts to do the same.) They spoke of their Ukrainian grandmother, the old farm, the Old Country. Their words filled the room around me like a thousand snapshot images. I grasped for something recognizable, something to seize and call my own.The idea I would ever feel legitimately connected to my heritage slipped away somewhere between the borsch and the knydli. I felt like an intruder, an imposter. Sitting in the midst of birthfamily tradition, I felt no less disconnected that I’d felt with adoptive family.

Growing up, my adoptive family graciously shared their traditions with me, but I lacked the bloodline to solidify it into a heritage. In reunion, my natural family genially accepted me into their bloodline, but I lacked the history bloodlines are meant to entail.

There are some things relinquishment and adoption tear apart that reunion just can’t piece back together. Part of the “adoption journey” entails letting go of the things we’ve lost, sorting out the carnage from the clash of fantasy versus reality and finding a balance between the person you might have been and the person you’ve become. At some point in the journey, you come to realize you can’t be given the things you are missing by an external force – or family. And, you learn to cherish the moments you are able to capture the sensation of historical and biological connectedness, even if its delivery is non-conventional.

That connectedness eluded me until the day I met Wyatt Earp . . .

(continue reading this piece here)

-

At 2:26 PM,

-

At 11:55 AM,

Saintly Jude: I think everyone approaches geneology research differently. For some (probably most) it is imperitive it be about bloodlines. For others, like the Captain, perhaps, it is more about the family story.

In the adoption community, how to denote adoptees in a family tree - and how to conduct "family tree projects" in grade school - is highly debated and will probably never be resolved.

My adoptive family actually had their tree published into a (very boring) non-fiction book. They are really, really into recording their history. In the book, my adoptive brother and I are not denoted as adopted. In all honesty, it probably would have upset me as a child had I been singled out as an adoptee. But, as an adult, it is my worst nightmare I'll one day open the door and find some traveling Norwegian couple standing on my porch, hoping to spend a week with their long-lost cousin. (A quite possible scenario, as there is a lot of traveling to and from Norway as family members try to expand their tree.) Ack! -

At 2:05 PM,

I understand exactly what you are saying, and I think it would be inapropriate for the Captain to slide his adopted grandchildren into the family tree as though we were their only family. Fortunately for them we have access to their family trees and he is amazing at hunting down family members. So their little branchs, fit into the big tree but are separate. He wants to do this so that when he is gone, we will all have access if we want to know where we came from, and where our adopted neices and nephews came from.

-

At 2:09 PM,

-

At 9:57 PM,

OK I finally managed to actually have time to read to the end. Wewhewwwww!!!! Fifteen minutes of peace!

Now I am sitting here wondering if it is the one glass of wine I drank or if this truly is one of the most profound moments of clarity about heritage and it's place in my life I have ever experienced. -

At 11:41 PM,

Oh wow.

I am in the very beginning stages of reunion. I know the feeling of wanting to belong. Of wanting that identity. I always envied those who had that familial history to cling to. I wanted it body and soul.

And I could see the similarities, physical and otherwise, that friends who were not adopted failed to see within their families.

Man, I wanted, more than anything, to belong like that.

Now that I'm in reunion, I still find myself looking for similarities with my bmom. It's unintentional, but there just the same.

Thank you for this post. It's made me think of and come to terms with that yearning in ways I'd never realized. -

At 1:29 PM,

First, my apologies for taking so long to respond. Blogger has been throwing fits for me for two days. Grrr.

Mia: Are you sure you only had one glass of wine? Seriously, your comments are too gracious and mean a lot to me. There is so much insight in your writing, too, so I guess we are helping each other in the process of looking at our own "stuff."

Andie: Welcome to my world - and to reunion. I've popped in and out of your corner of the web in the last week or so as well (I love the title of your blog). I am always hesitant to interject my thoughts when someone is sharing their new reunion because I remember what a whirlwind, emotional time it is. But, please know I've been reading and rooting you on for a safe journey.

How strange it is to hear you talking about this subject. Today I sat with the Captain, (my dad), as he was searching on the internet for some of his ancestors. As I sat there I was aware that I didn't actually know the names he was searching for, they didn't ring a bell. As it turns out he was actually looking for the great grandparents of one of his 'adopted' grandchildren. Their families are then seemlessly added onto our family tree as another branch. They are as he sees it, his family too and therefore should be present. This he sees as our heritage, with all of the branchs and they all have importance. However the one differentiating factor for his 'adopted' grandchildren are that in most cases they do know something of their origins.